On March 27th, the 2020 live-action remake of Mulan was expected to make history as the second Disney film directed by a woman with a budget of over $100 Billion. Unfortunately, the release has been pushed back to July 24th due to COVID-19 (at this point, who knows if that date will stick).

Starting when trailers were released last year, decisions to cut much-beloved characters such as Mushu and Li Shang caused controversy. Additionally, the upcoming 2020 film will not be a musical, and it will be missing many iconic scenes. Among them is the one where Mulan dramatically cuts her hair with a sword.

Initially, I was disappointed by these changes, but I have since learned that they were made to rectify some cultural missteps from the 1998 retelling of the legend of Mulan. The film aims to be more faithful to the Ballad of Mulan (AKA Ode of Mulan), a poem from the Wei Dynasty (386–534 AD) which details the story of 花木兰 (Hua Mu Lan), a girl who cross-dresses as a man to take her father’s place in the army. Over the years, this legend has been retold and adapted in literature, movies, TV, and even video games. Disney’s 1998 version of the story has come under criticism for inaccurately portraying Chinese culture.

Which Disney Princess are you? (I’m always Mulan)

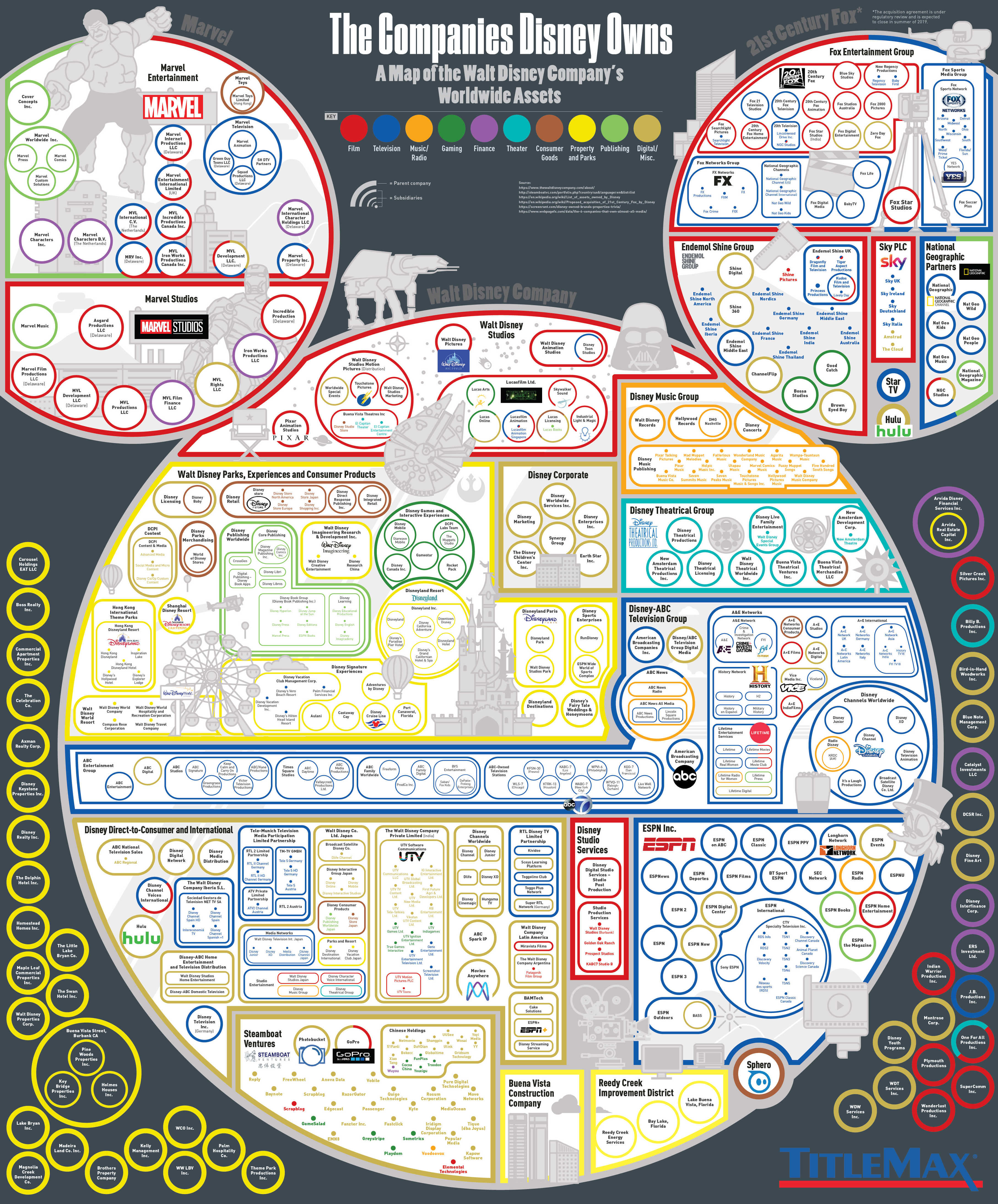

Stories aren’t just stories. According to this handbook on child development and media done by Dr. Sherryl Graves, children use television to learn about ethnicity. After the March 2019 Disney-Fox Merger, Disney owns a historic 36% of the movie market. In Rosina Lippi-Green (Ph.D.)’s 2012 book, English with an Accent, she argues that the interrogating Disney’s linguistic and cultural messages are important precisely because they capture such a large share of the market. Producers of these films have “almost unquestioned access to children” with little oversight. In our current era of quarantine, the amount of time kids spend streaming from services like Disney+ has only gone up.

Developed by TitleMax.com

In short, Disney’s representation of people of color and culture matters. It matters not only in children’s understanding of other cultures/ethnicities, but it also plays in self-conceptualization.

Mulan is Disney’s only Chinese princess. For some, the film is their first exposure to Chinese culture. I have college-age friends who have told me that Mulan was their only point of reference for what life is like in China. As a child, I went to sleepaway camp. Armed with flashlights and extra blankets, we would huddle around, talk about boys, and speculate who our counselors were dating. On multiple occasions, we’d go around and say which Disney Princess everyone was. I was always Mulan.

Deformations and Restorations

When Disney adapted the legend of Mulan, it borrowed linguistic elements, cultural ideas, and styles from China. In the process, it also distorted many of these borrowings into something unrecognizable to a Chinese audience. This was analyzed by Professors Mingwu Xu and Chuanmao Tian as a process of cultural deformation and reformation.

In cultural deformation, the original culture is “decontextualized” and “universalized” in an attempt to make it more palatable to an American audience. When Mulan was translated and dubbed in Mandarin Chinese, translators had to restore some of these borrowings. This included more benign instances such as correcting the speech of the emperor or removing spoken references to Western snacks like corn chips.

However, other cultural deformations were more serious. Translators were also careful to replace references to Western conceptions of miracles to references to Chinese folk religion. For example, in the original, after Mulan accidentally picks a fight with Yao, Chien Po calms him down with a seemingly meaningless chant: “Ya Mi Ah To Fu Da”. In the Chinese version, this is restored to a Buddhist formula, ‘南无阿弥陀佛’ (Nan Wu Ah Mi Tuo Fo, Namo Amitabha).

Even the name of the enemy, the Huns, is a deformation. In the original ballad, the name for the invaders is not specified, though historically, it should be the 柔然 (rouran). This people group was the first to refer to their leader using the title “Khan”, the name given to Mulan’s horse. The historic Huns never invaded China. In the Chinese dub, the invaders are the 匈奴(xiongnu), speculated predecessor of the Huns. Still not the 柔然 (rouran), but at least the 匈奴 (xiongnu) did actually invade China.

What about Mushu?

Mushu is a particularly poignant example of cultural deformation from the 1998 version of Mulan. In Chinese culture, dragons are lucky and a positive association. This is almost completely opposite to the conception of dragons in the West, where they are usually depicted as monsters. According to Chinese legend, dragons were the ancestors of the Chinese people, particularly the emperor. In Mulan, this symbol of power and ancestral roots is trivialized into lizard-sized caricature who speaks a stigmatized variety of English.

Since I’m pretty Americanized, I didn’t find it that problematic as a kid. In contrast, when the dub was released in China, many felt that their culture was being trivialized. This example is particularly interesting because it can’t be fixed without fundamentally changing the graphics/major portions of the movie. Fixing things in the dub can only get you so far when it comes to cultural representation.

Hope for Mulan 2020?

Based on official trailers of the live-action remake, the 2020 film looks promising. Mulan has preexisting martial art prowess and training. According to Executive Producer Barrie Osborne, she will have “lots of moments where she proves [herself]”. This is more consistent with the original ballad, in which she serves in the military for 12 years.

Decisions have already been made in the name of cultural sensitivity. For example, a kiss between Mulan and her love interest in the movie was edited out because of reservations from the Chinese office. The decision to omit Mushu because of cultural concerns has also given some people hope that this retelling of the legend will feature better female representation.

However, the trailers have already been criticized for historical inaccuracy by its Chinese audience. The “tuluo” house that Mulan lives in is characteristic of neither the time nor place the movie is set. This leads me to speculate that even the 2020 version will fall prey to sacrificing historical accuracy for a Chinese vibe. This same line of thinking likely motivated the 1998 version to include the completed and contemporary Great Wall of China (which wasn’t finished until 1878).

For all its talk about historical accuracy, the re-branded antagonist (Bori Kahn) has a partner who is a witch and shape-shifting woman/bird. The trailer also features a phoenix.

It remains to be seen how the 2020 live-action film will tackle the larger cultural problems such as the portrayal of honor and shame. Regardless, the trailer features Mulan riding into war shaking out her long black hair, dodging arrows, and speaking in her normal (rather falsely deep) voice. Perhaps she will bring honor to us all.

No Comments